This interactive map shows the location of language varieties belonging to the West-Coastal Bantu (Vansina 1995; Bostoen et al. 2015) a.k.a West-Western branch (Grollemund et al. 2015) of the Bantu language family. Each point on the map represents a set of geocoordinates for a given language/dialect/variety. Users may select two display options within the interactive map: “Phylogenetic Classification” or “Referential Classification”.

Phylogenetic Classification

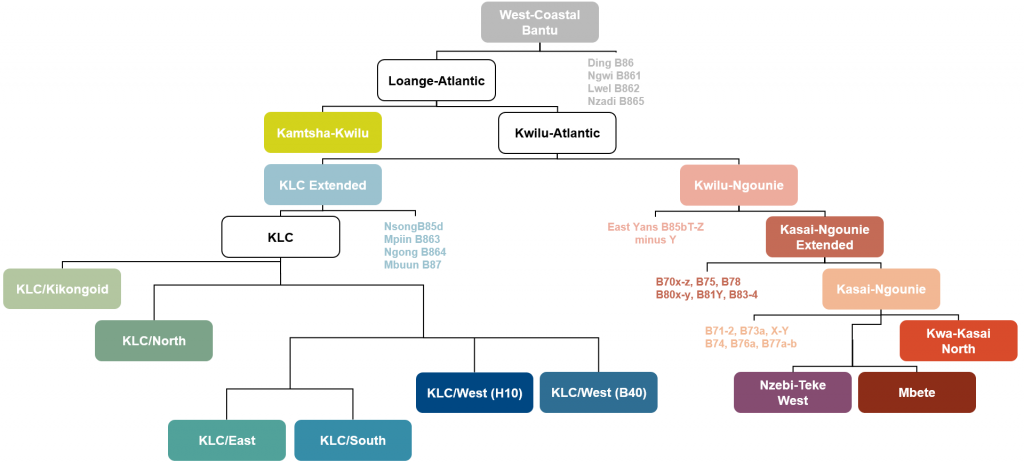

The option “Phylogenetic Classification” displays our present understanding of the internal genealogical classification of the West-Coastal Bantu (WCB)/West-Western Bantu (WWB) branch. Varieties are color coded according to the branch to which they belong in the thus far most comprehensive lexicon-based phylogeny of WCB (Pacchiarotti et al. 2019). The internal structure of the WCB subbranch known as the Kikongo Language Cluster (KLC) is based on de Schryver et al. (2015) and Bostoen and de Schryver (2018a; b).

A simplified version of the latest WCB internal classification according to Pacchiarotti et al. (2019) is given in the tree accompanying the phylogenetic map. The colors of individual language varieties in the map match the colors of the main subgroups to which they belong within the tree. In the tree figure, “monophyletic” means that languages form a group or grade proper with a most recent common ancestor which is different from that of other monophyletic groups. “Paraphyletic” means that the language varieties in question do not have a more recent common ancestor other than either WCB itself (e.g. Nzadi, Lwel, Ngwi and Ding at the top of the tree) or one of its subclades (e.g. several B70 Teke varieties whose most direct recent ancestor is the one of all Kasai-Ngounie languages).

Referential Classification

The option “Referential Classification” assigns a different color to each of Guthrie’s (1971) non-genetic, geographically/typologically-based groups which we now know to be part of the WCB/WWB branch. The alphanumeric code assigned to each variety corresponding to a set of coordinates is based on Guthrie (1971) and further updates in Maho (2009) (see also Guthrie 1948, 1953 for language maps). Codes with two or three digits optionally followed by lowercase a, b, c, d, e and uppercase F are from either Guthrie (1971) or Maho (2009). Additionally, we came up with the following conventions to maximally distinguish among languages/varieties/dialects not inventoried in Guthrie (1971) or Maho (2009).

Legend for Non-KLC WCB varieties:

- Decimal number where the second digit is zero followed by (lowercase) ‘x’, ‘y’ or ‘z’, e.g. Boma Nkuu (Monkana) B80x, Boma (Nkuu) South (Boku) B80y. We use this convention to indicate that a given variety is not inventoried in either Guthrie (1971) or Maho (2009) and we tentatively place it in one of Guthrie’s groups. For example, lowercase “x” in “B80x” indicates that Boma Nkuu (Monkana) is a variety not previously inventoried; “B80” in “B80x” means that we are tentatively placing it within Guthrie’s B80 group based mostly on the geographical location of Boma Nkuu speakers. Lowercase “x” and “y” in B80x and B80y also mean that we consider Boma Nkuu (Monkana) and Boma (Nkuu) South (Boku) to be two distinct languages, rather than dialectal variants of a single language.

- Decimal number where the second digit is not zero followed by (uppercase) ‘X’, ‘Y’ ‘Z’, etc., e.g. Mbuun (Mayungu) B87X, Mbuun (Mwilambongo) B87Y, Lwel East (Sedzo) B862X. With capital X, Y, Z, we indicate that we have data on a variety inventoried in Guthrie (1971) and/or Maho (2009) coming from more than one geographical location and that we consider these data to be dialectal varieties of the same language, e.g. B87X and B87Y are two dialects of Mbuun B87. We used this convention also when we had data on a variety from one single geographical location but we were able to gather additional dialectal information on that variety, cf. Lwel East (Sedzo) B862X, where X indicates the eastern variety of Lwel

Conventions in a) and b) can also be combined, e.g. Boma Yumu (Pentane/Mondai) B80zX and Boma Yumu (Saio) B80zY. “B80z” means that both varieties are instances of the un-inventoried language “Boma Yumu”. Capital “X” and “Y” after B80z mean that they are two distinct dialectal varieties of Boma Yumu. Conventions in a) and b) can also be combined with Guthrie (1971)/Maho (2009) codes, e.g. Mpur (Due) B85eY and Mpur (Kolonzadi) B85eZ. Capital “Y” and “Z” after Maho’s (2009) code for Mpur B85e mean that B85eY and B85eZ are two dialects of B85e.

Legend for KLC WCB varieties:

- Guthrie/Maho codes for the KLC have been copied from Maho (2009), unless they end in a capital ranging between V and Z. In this case, the variety not mentioned in Maho (2009). We have attributed them the Guthrie/Maho code of the variety/ies to which they are most closely related according to the phylogenetic classification in Bostoen and de Schryver (2018a).

References

Bostoen, Koen, Bernard Clist, Charles Doumenge, Rebecca Grollemund, Jean-Marie Hombert, Joseph Koni Muluwa & Jean Maley. 2015. “Middle to Late Holocene Paleoclimatic Change and the Early Bantu Expansion in the Rain Forests of West Central-Africa”. Current Anthropology 56.354-384

Bostoen, Koen & Gilles-Maurice de Schryver. 2018a. “Langues et évolution linguistique dans le royaume et l’aire kongo”. Une archéologie des provinces septentrionales du royaume Kongo ed. by Bernard Clist, Pierre de Maret & Koen Bostoen, 51-55. Oxford: Archaeopress. (Online file)

Bostoen, Koen & Gilles-Maurice de Schryver. 2018b. “Seventeenth-Century Kikongo Is Not the Ancestor of Present-Day Kikongo”. The Kongo Kingdom: The Origins, Dynamics and Cosmopolitan Culture of an African Polity ed. by Koen Bostoen & Inge Brinkman, 60-102. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

de Schryver, Gilles-Maurice, Rebecca Grollemund, Simon Branford & Koen Bostoen. 2015. “Introducing a State-of-the-Art Phylogenetic Classification of the Kikongo Language Cluster”. Africana Linguistica 21.87-162. (Online file)

Grollemund, Rebecca, Simon Branford, Koen Bostoen, Andrew Meade, Chris Venditti & Mark Pagel. 2015. “Bantu Expansion Shows That Habitat Alters the Route and Pace of Human Dispersals”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112.13296-13301. (Online file)

Guthrie, Malcolm. 1948. The Classification of the Bantu Languages. London; New York: Oxford University Press for the International African Institute.

Guthrie, Malcolm. 1953. The Bantu Languages of Western Equatorial Africa. (Handbook of African languages). London; New York: Oxford University Press for the International African Institute.

Guthrie, Malcolm. 1971. Comparative Bantu: An Introduction to the Comparative Linguistics and Prehistory of the Bantu languages. Volume 2: Bantu Prehistory, Inventory and Indexes. London: Gregg International.

Maho, Jouni Filip. 2009. NUGL Online: The Online Version of the New Updated Guthrie List, a Referential Classification of the Bantu Languages (4 Juni 2009). (Online file)

Pacchiarotti, Sara., Natalia Chousou-Polydouri, Koen Bostoen. 2019. “Untangling the West-Coastal Bantu mess: identification, geography and phylogeny of the Bantu B50-80 languages” Africana Linguistica 25.155–229. (Online file)

Vansina, Jan. 1995. “New Linguistic Evidence and the Bantu Expansion”. Journal of African History 36.173-195.